Lord Byron (1788-1824)

|

|

Maid of Athens

Athens, 1810 Maid of Athens, ere we part, Give, oh give me back my heart ! Or, since that has left my breast, Keep it now, and take the rest ! Hear my vow before I go, Ζωή μου σας αγαπώ! By those tresses unconfined, Woo'd by each Ægean wind; By those lids whose jetty fringe Kiss thy soft cheeks' blooming tinge; By those wild eyes like the roe, Ζωή μου σας αγαπώ! By that lip I long to taste; By that zone-encircled waist; By all the token-flowers that tell What words can never speak so well; By love's alternate joy and woe, Ζωή μου σας αγαπώ! Maid of Athens ! I am gone: Think of me, sweet ! when alone. Though I fly to Istambol, Athens holds my heart and soul: Can I cease to love thee? No ! Ζωή μου σας αγαπώ! |

|

Near the end of English Bards, and Scotch Reviewers, Byron had scoffed at Thomas Bruce, Earl of Elgin’s waste of money on the "Phidian freaks, / Mis-shapen monuments and maimed antiques" he was removing from the Acropolis and shipping to England. Now, the Parthenon and other ruins of Greece’s golden age, to be seen everywhere, increasingly filled Byron with sorrow, while the despoliation of Greece’s treasures and its people’s enslavement by the Turks fueled his indignation. His anger at the ignoble Elgin would flash forth in Childe Harold and in The Curse of Minerva. Excursions in 1810 to Cape Sounion and to Marathon, where the Athenians defeated the invading Persians in 490 BC, reinforced for him the appalling contrast between the glory and might of ancient Greece and its present disgrace under Turkish domination. He movingly evoked these scenes and sentiments a decade later in the often-quoted stanzas on "The Isles of Greece" and on Marathon in Don Juan.

In March 1810 Byron and Hobhouse extended their tour into Turkey. In Smyrna, he completed the second canto of Childe Harold, incorporating his adventures in Albania and his thoughts on Greece. During the two months he spent in Constantinople amid Oriental splendor, filth, and cruelty, his distaste for the Turks grew. In July he traveled back to Athens, where he settled in the Capuchin monastery by the Choragic Monument of Lysicrates, below the Acropolis. He studied Italian and modern Greek and moved easily in the cosmopolitan society of Athens.

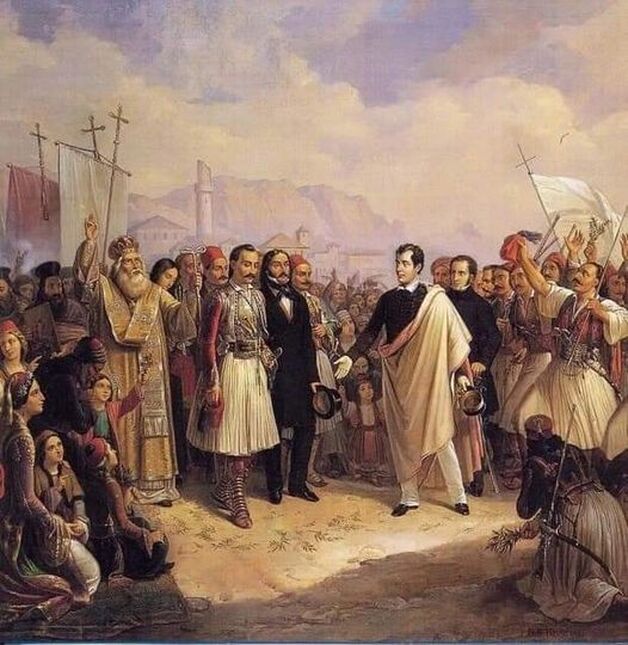

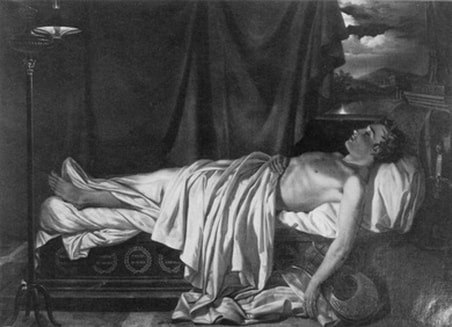

Within 1811, he wrote The Curse of Minerva, attacking Lord Elgin for pillaging Greece’s heritage, records the full extent of Byron’s sympathy for classical Greek culture as well as for modern Greece and her people. When he sailed for England in April 1811, he traveled for a time aboard the transport ship Hydra, which also carried the last large shipments of Lord Elgin’s marbles. To Augusta he wrote that he had probably acquired nothing by his travels but "a smattering of two languages and a habit of chewing Tobacco," but this claim was disingenuous. "If I am a poet," he mused, "... the air of Greece has made me one." He had accumulated source material for any number of works. More, exposure to all manner of persons, behavior, government, and thought had transformed him into a citizen of the world, with broadened political opinions and a clear-sighted view of prejudice and hypocrisy in the "tight little island" of England. Within weeks of his return, Byron was plunged into a period of prolonged mourning. His mother died on 2 August. News of the deaths of two classmates followed. Then, in October, he learned of the death from consumption of John Edleston, the former choirboy at Trinity College. Deeply affected, he lamented his loss in the lines "To Thyrza" (1811), a woman’s name concealing the subject’s true identity and gender. This was the first of several "Thyrza" poems. In January 1812 Byron resumed his seat in the House of Lords, allying himself with the Liberal Whigs. During his political career he spoke but three times in the House of Lords. On March 1812 Murray published Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Cantos I and II. Shortly after Childe Harold appeared, Byron remarked, "I awoke one morning and found myself famous." In less than six months sales had reached forty-five hundred copies. Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, Cantos I and II, can be read as Byron’s poetic journal of his Mediterranean and Eastern tour in 1809-1811. Color and energy animate descriptions of the familiar (Spain and Portugal), the exotic (Albania and Greece), and the violent (a Spanish bullfight and feuding Albanians). The poem is the record of the contemporary quest for moral and intellectual certainty and positive self-assertion. In Childe Harold Byron began to blend narration and digression to produce a type of descriptive-meditative poetry which he would use to greater advantage in Don Juan. Scenes Harold and the narrator describe often spur them to moral reflections. Sites associated with the Napoleonic campaign, elicit comments on the follies of war (Canto I); the ruins of Greece evoke thoughts on the evils of tyranny and on the transience of powerful civilizations and "men of might" (Canto II). The work repeatedly stresses the rich heritage of poetry and liberty which contemporary Europe has received from classical Greece. The country’s ancient greatness serves as a standard by which modern Greeks are measured. Harold was introduced, Byron wrote in the preface, "for the sake of giving some connection to the piece." By labeling Harold "a fictitious character" Byron sought to dissociate himself from his protagonist, but his readers, noting many and striking similarities, persisted in equating the artist with his hero. The drawing rooms and salons of Whig society vied for Byron’s presence and lionized him. He met the spirited, impulsive Lady Caroline Lamb, who initially judged him "mad—bad—and dangerous to know." Their tempestuous affair lasted through the summer, until Byron rejected her. Despite its outcome, his connection with Lady Caroline left him on friendly terms with her mother-in-law, the witty Lady Melbourne. He proposed marriage to her niece, Annabella Milbanke, as a possible means of escaping the insistent Caroline. A twenty-year-old bluestocking, she was widely read in literature and philosophy and showed a talent for mathematics. She declined the proposal in the belief that Byron would never be "the object of that strong affection" which would make her "happy in domestic life." By November he was conducting an affair with the mature Lady Oxford, a patroness of the Reform Movement. Between June 1813 and February 1816, Byron completed and had published six very popular verse tales, five of them influenced by his travels in Greece and Turkey: The Giaour (1813), The Bride of Abydos (1813), The Corsair (1814), Lara (1814), and The Siege of Corinth and Parisina (1816). In June 1813 Byron began an affair with his 29-year-old half sister, Augusta. Married since 1807 to her spendthrift cousin, Colonel George Leigh, she had three daughters. While no legal proof exists, evidence in Byron’s letters to his confidante Lady Melbourne strongly suggests an incestuous connection. Through poetry he found relief from his involvement with Augusta and from an inconclusive flirtation in the autumn of 1813 with Lady Frances Wedderburn Webster. In December Byron produced a third Oriental tale, The Corsair. On the day of publication ten thousand copies were sold, "a thing," Murray excitedly assured him, "perfectly unprecedented." On 10 April 1814, amid rumors of the abdication and exile of the emperor Napoleon, Byron wrote and copied Ode to Napoléon Buonaparte. On the 16th it was published anonymously, though the inscription to Hobhouse revealed its parentage. Since Harrow, Byron had had mixed feelings about Napoleon. He admired the titanic qualities of the brilliant strategist, dynamic soldier, and statesman, but he was repelled by his brutal conquest of Iberia and his perversion of liberal ideals. On 15 April 1814 Augusta gave birth to a girl, Elizabeth Medora. When Medora Leigh grew up, she believed herself to be Byron’s daughter, though Byron never acknowledged the paternity, as he did for his other illegitimate off-spring. Byron spent much of the summer of 1814 with Augusta, while continuing to correspond with Annabella. After inauspicious hesitations and postponements, Byron married Annabella on 2 January 1815. Byron resumed work on the Hebrew Melodies, lyrics for airs Jewish composer Isaac Nathan was adapting from the music of the synagogue. In April, after a tempestuous visit with Augusta, Lord and Lady Byron settled in the Duchess of Devonshire’s London house. That same month, Isaac Nathan published A Selection of Hebrew Melodies, with Byron’s verses and Nathan and John Braham’s music. Despite the high price for a thin folio, the work sold ten thousand copies in two editions. In the summer, Murray brought out the poetry separately as Hebrew Melodies. Throughout 1815 financial problems and heavy drinking drove Byron into rages and fits of irrational behavior. When Annabella was in an advanced stage of pregnancy, he made her the scapegoat for his troubles. On December 10, 1815, she gave birth to Augusta Ada Byron. Because of his anger and violent utterances, Lady Byron concluded that her husband was mentally deranged, so on January 15 1816, she and Augusta Ada left London. He never saw them again. In February Murray published The Siege of Corinth and Parisina in a single volume. The anonymous first edition sold six thousand copies. On March 17 the terms for the legal separation were agreed upon. During this crisis, Byron had a casual liaison with Claire (Jane) Clairmont, the stepdaughter of philosopher William Godwin and the stepsister of Mary Godwin, with whom Percy Bysshe Shelley had eloped in 1814. Byron signed the final deed of separation on April 21, having decided to go abroad with the completion of this formality. On his trip he was accompanied by Fletcher the valet, his personal physician, Dr. John Polidori ("Pollydolly"), Robert Rushton, and a Swiss servant. Byron would never see England again. The party reached Geneva on May 25 1816. Byron was unaware that waiting for him were Claire Clairmont, pregnant with his child, Shelley, and Mary Godwin. A genuine friendship and mutual high regard flourished between the two poets. They passed the time agreeably by boating on Lake Leman and conversing at the Villa Diodati, which Byron had rented, with its commanding view of the lake and the Juras beyond. Byron completed the third canto of Childe Harold. Byron despised wars of aggression waged for personal gain while championing as honorable those conflicts that defended freedom, such as the battles of Marathon and Morat and the French Revolution. July 1816 represents a remarkably creative month for Byron. Among other pieces written at this time appear three notable short poems. "The Dream" traces his emotional development from idealism to despair in his love for Mary Chaworth; "Darkness" imagines the last days of the disintegrating universe; "Prometheus" celebrates the triumph of the defiant spirit over torture. The arrival of Hobhouse coincided with the departure of Shelley, Mary, and Claire, who returned to England with the manuscripts of the third canto of Childe Harold. On January 12 1817, Claire gave birth to a daughter Byron named Clara Allegra, and called by her second name. After four months in Switzerland, Byron, accompanied by Hobhouse, lumbered toward Italy in October 1816. Following a sojourn in Milan, they reached Venice the next month. He began an affair with Marianna Segati, his landlord’s wife, attended the conversazione of Countess Isabella Teotochi Albrizzi, the center of Venetian literary-social life, and studied Armenian at a monastery on the island of San Lazzaro. Murray published Childe Harold, Canto III, on November 18, and The Prisoner of Chillon, and Other Poems on 5 December. Within a week of publication, seven thousand copies of each volume had been sold. Byron set out in mid April 1817 to join Hobhouse in Rome. In Ferrara, his visit to the cell where the 16th c. poet Torquato Tasso had been confined for madness inspired an impassioned dramatic monologue, The Lament of Tasso. Byron was "delighted" with the Eternal City. He settled in mid June at the Villa Foscarini at La Mira on the Brenta, seven miles from Venice. Here, he began to distill his memories of Rome into poetry. Late summer 1817 marks a significant development in Byron’s literary career. Ηe heard about the return of a supposedly deceased husband to his Venetian wife; she had meanwhile taken a lover, and then had to choose her husband, her lover, or solitary life on a pension. At this time, he happened to see John Hookham Frere’s Whistlecraft (1817), a mock-heroic satire in ottava rima modeled on the Italian burlesque manner. The seriocomic mood, colloquial style, and digressions of ottava rima, no less than his fondness for couplets in his Popean satires, attracted Byron to this verse form as the medium for his witty version of the story of Venetian customs and light morals. By October 10 he had finished Beppo. His new poem, he assured Murray, would show the public that he could "write cheerfully, & repel the charge of monotony & mannerism." Murray published Beppo, A Venetian Story, without Byron’s name on the title page, on February 28 1818, to immediate success. The Monthly Review (March 1818) found Byron’s "satire, though at times a little tinged with vulgarity, ... usually good-humored and often well pointed." In the Edinburgh Review (February 1818), Jeffrey commended "the matchless facility" with which the "unknown writer" "cast into regular, and even difficult versification ... the most light, familiar, and ordinary conversations." The author’s "digressions and dissertations" —the bulk of the poem— formed its "most lively and interesting part." Jeffrey even suggested that the anonymous poet had "caught a spark from the ardent genius of Byron." On April 28 1818 Murray brought out Childe Harold, Canto IV; the five printings of the first edition comprise ten thousand copies. In the Quarterly Review (April 1818) Scott judged that the last part of "this great poem ... sustained Lord Byron’s high reputation," though it possessed less passion and more "deep thought and sentiment" than the earlier cantos. Early in June Byron moved into the Palazzo Mocenigo, his spacious residence overlooking the Grand Canal, within sight of the Rialto Bridge. Living with him was his daughter Allegra (brought to Venice by the Shelley party in April), whom he had agreed to support and educate. Here, too, he lodged his fourteen servants, a menagerie, and a veritable harem. In a 1818 letter to Murray he mentioned that he had completed an ode on Venice, and that he had "two stories -one serious & one ludicrous not yet finished- and in no hurry to be so." The "serious" poem was Mazeppa, a Cossack verse tale of illicit love and a wild horseback ride. The "ludicrous" one was the lengthy first canto of his comic epic Don Juan. Over the next five years Byron added fifteen more cantos to the poem, leaving a seventeenth unfinished at his death. In November he sent Murray the canto along with Mazeppa (published in June 1819 with Ode on Venice), and soon was at work on Canto II, an account of Juan’s sea voyage, shipwreck, and rescue by Haidée. Hobhouse and other friends in England praised the poetry and satire in Don Juan, Canto I, but voiced alarm at its indecencies and attacks on religion, writers, and Lady Byron (in the character of Donna Inez, Juan’s "mathematical" mother). They urged that the manuscript be suppressed. Murray was willing, and eager, to publish the piece, especially if some of the "indelicacies" were omitted. But Byron would have none of his "damned cutting and slashing"; the poem would succeed or fail on its own merits. Byron, exhausted by debauchery, cut and slashed in his personal life, getting rid of "La Fornarina" and his harem. In early April 1819 at the Benzoni conversazione, he encountered the Countess Teresa Guiccioli, whom he had met casually. Now nineteen, she had been married for just over a year to a rich count of 58. A strong mutual attraction quickly developed between Byron and Teresa. Having given up "miscellaneous harlotry," he settled for "strictest adultery" as cavalier servente to Teresa, his "last attachment." For the next four years, until his departure for Greece in July 1823, they lived in several Italian cities and towns as dictated by her husband, by her health and desires, and, after her separation from her husband in July 1820, by her father. On July 15 1819, Murray cautiously published the first two cantos of Don Juan in an expensive quarto format of 1,500 copies. By tacitly admitting, through anonymous publication, that Don Juan was disreputable, Murray intensified the outcry against the work. The critics hit back with a fury virtually unprecedented, vilifying both poet and poem. Byron’s serious poems and Childe Harold had given but limited voice to his complex personality; his comic masterpiece Don Juan permitted him full expression. It is at once a satire on his age, a picaresque novel in poetry, and arguably the greatest verse epic in English since Paradise Lost. The dazzling range of subjects, incidents, and moods in his "versified Aurora Borealis", and its geographical sweep, no less than its genre, justify his claim that "My poem’s epic". The stanzas teem with Byronic observations on liberty, tyranny, war, love, hypocrisy, cant, and much more. The landscape stretches from Juan’s native Spain across the Mediterranean to the Greek Cyclades, up to Constantinople and on to Russia, with a digression to Kentucky, before stopping in England. Byron’s literary models include the classical epics of Homer and Virgil and the Renaissance Italian epics of Ariosto and Tasso. To Moore, his visitor in October, he presented the manuscript of his memoirs, begun in Venice the previous year and not to be published during Byron’s lifetime. They were intended to be "Memoranda—and not Confessions," containing, among other things, "a detailed account" of his marriage and its "consequences." Moore sold them to Murray three days after news of Byron’s death reached England, Hobhouse and Murray, over Moore’s objections, had the memoirs burned in Murray’s parlor to protect Byron’s reputation from his indiscretions. On December 28 1820 Byron sent to England the fifth canto of Don Juan retailing Juan’s adventures. Moore received additional pages of Byron’s memoirs. In April 1821 Murray published in a single volume Marino Faliero and The Prophecy of Dante. The critics thought the drama failed as play and poem. Without Byron’s permission, Marino Faliero was given seven performances at Drury Lane in April and May 1821, the only one of his plays acted in his lifetime. Adaptations of Sardanapalus and Werner (1823) enjoyed great success on the 19th-century stage. With the completion of The Two Foscari in July, Byron began work on Cain, A Mystery, its subtitle an allusion to the medieval dramas on biblical themes and, he told Moore, "in honor of what it probably will remain to the reader." Grounding his play in the Old Testament and 18th-century rationalism, Byron challenged accepted religious beliefs in good, evil, death, and immortality. Byron had placed his daughter Allegra in a convent school in Bagnacavallo in March 1821; on April 20 1822 she died there at the age of five, after a brief illness. In November Byron agreed to loan four thousand pounds to the Greek fleet. In January 1824 he joined Prince Alexander Mavrokordátos on the mainland in swampy Missolonghi. Wearing his red military uniform, Byron was enthusiastically welcomed by shouts, salutes, and salvos. On the eve of his birthday, he turned once more to poetry to express his inner feelings on his life and the principles of freedom; the ten stanzas of "On This Day I Complete My Thirty-Sixth Year" constitute one of his last poems. Over the next three and one-half months, all occasions —military, political, physical, climatic, and amorous— seemed to conspire against him: his leadership of a planned attack on the Turkish stronghold at Lepanto was postponed for lack of fighters; factions still prevented a unified war effort; his constitution, weakened by years of dieting to combat congenital portliness, deteriorated under the constant strain and the cold winter rains in Missolonghi; the emotional frustration of his unrequited love for his handsome fifteen-year-old page boy, Loukas Chalandritsanos, seems to have inspired his final poem (posthumously titled and published as "Love and Death"). Despite uncertainty and reverses, he continued to commit money and energy to the Greek cause. On April 9, having been soaked by a heavy rain while out riding, Byron suffered fever and rheumatic pains. By the 12th he was seriously ill. Repeated instances of bleeding, which he initially resisted, further debilitated him. On Easter Sunday, he entered a comatose state. At six o’clock on the evening of Easter Monday, April 19 1824, during a violent electrical storm, Byron died. His body arrived in London on June 29, and for two days lay in state. On Friday, July 16 1824, Lord Byron was buried in the family vault beneath the chancel of Hucknall Torkard Church near Newstead Abbey.

|

The fame to which Byron awoke in London in 1812 spread rapidly throughout the world by scores of translations and editions. He was delighted to see his merits argued in a Java gazette in 1814, and gratified some years later to find himself described as "the favorite poet of the Americans." His influence was pervasive and prolonged. Philosophically and stylistically, Byron stands apart from the other major Romantics. He was the least insular, the most cosmopolitan of them. Poetic imagination was not for him, as for them, the medium of revelation of ultimate truth. In narrative skill, Byron has no superior in English poetry, save Geoffrey Chaucer; as Ronald Bottrall notes, Byron, like his illustrious predecessor, could "sum up a society and an era." His subjects are fundamental ones: life and death, growth and decay, humankind and nature. His "apotheosis of the commonplace" is, to Edward E. Bostetter, "one of his great contributions to the language of poetry." Lacking the inhibitions of his contemporaries, Byron created verse that is exuberant, spontaneous, expansive, digressive, concrete, lucid, colloquial—in celebration of "unadorned reality."

"I was born for opposition," Byron proclaimed in Don Juan. The outstanding elements of his poetry both support his self-analysis and insure his enduring reputation. As a major political and social satirist, he starts, in the Classical and Augustan manner, with a fixed standard of judgment, then, in either seriocomic or savage tones, repeatedly denounces war, tyranny, and hypocrisy. As an untiring champion of liberty, he firmly believed that "Revolution / Alone can save the earth from hell’s pollution".

In 1888 D. Skylitsis, President of the Society of Friends of Lord Byron, proclaimed a competition for the creation of a statue honoring Byron. Renowned artists of the time took part, and the work of Lazaros Sohos, an important Greek sculptor, was selected and exhibited at Zappeion. He is the same artist who created Kolokotronis, on Stadiou Street, Syntagma area.

However, the sponsor awarded the composition to the French sculptor Henri Michel Antoine Chapu to the dismay and anger of the Greek competitors. The sculptor, though, died before he ever completed the work, so the work in marble was executed by Jean Alexandre Joseph Falquiere and placed in the corner of Vas. Amalias and Vas. Olgas Avenues on the grounds of the Zappeion Gardens. It was inaugurated in July 1895 in time for the Olympic Games of 1896. In the monument, Greece is depicted as a seated half-naked woman larger than life and larger than Lord Byron. She demonstrates her gratitude to Byron by placing a branch of a palm tree over his head, a symbol of immortality. Byron, in turn, is depicted as a young beardless round-faced youth, wearing fine European clothes and boots. The semi-reclining male figure on the back side symbolizes the Greek nation under seize. The composition rests over a round scaled base, its highest point being three meter tall. The composition came to be known as "Byron's Statue" but the official title is «Η Ελλάς (ευγνωμονούσα) τον Βύρωνα» or "Greece (expressing her gratitude) to Byron". It is no coincidence that on the location of the Statue to Byron was the tram stop to the neighborhood called Byron, in his honor, but also that in a direct line one can see the Monument to Lysicrates, where Byron lived during his stay in Athens. Close by, Byronos Street links the historic district of Plaka to the Dionyssiou Areopagitou pedestrian street. HOME | TOURS | CHURCHES | CITY BREAKS | DESTINATIONS | MUSEUMS | RESOURCES | FOOD | SIGHTSEEING | TRAVEL

|